Happy and Healthy New Year

Recent posts:

Global economic growth accelerates at end of 2019

The rate of global economic expansion accelerated for the second successive month in December, hitting its highest level since April 2019. The uptick was underpinned by stronger inflows of new work, rising employment and improved business optimism. International trade remained a drag on growth, however, as new export orders contracted for the thirteenth successive month.

The J.P.Morgan Global Composite Output Index – which is produced by J.P.Morgan and IHS Markit in association with ISM and IFPSM – rose to an eight-month high of 51.7 in December, up from 51.4 in November. The headline index has posted above the neutral 50.0 mark that separates expansion from contraction in each of the past 87 months.

Output growth was recorded in both the manufacturing and service sectors during December. The rate of expansion in manufacturing production eased, as downturns in the intermediate and investment goods sub-industries offset solid growth at consumer goods producers. Business activity at service providers rose at the fastest pace in five months, with expansions seen across the business, consumer and financial services industries.

December saw economic activity increase in the US, China, the euro area, India, Brazil and Russia. Contractions were registered in the UK, Australia and Italy. Output in Japan also decreased slightly, according to Flash PMI data, to extend its downturn into a third successive month.

The level of incoming new business rose at the fastest pace in five months in December. Manufacturing new orders rose only marginally, whereas growth at service providers accelerated to its best since July 2019. (…)

Only a handful of countries are in good and improving manufacturing mode, however.

We all wish we had 2020 vision but one’s vision can be affected by one’s narrative. This is what investors need to understand early in 2020 as two critical data sets are floating around and are discriminately used by some pundits based on their own particular narrative.

U.S. PMI and earnings data vary significantly depending on which supplier/aggregator one chooses.

This chart from Axios (Dissecting the U.S. manufacturing divergence) shows the significant divergence between the ISM and Markit U.S. manufacturing PMIs. Bearish analysis will use the ISM which infers a deepening manufacturing recession while the more positive views will highlight the turnaround in IHS Markit’s PMI.

Data: IHS Markit, ISM; Chart: Andrew Witherspoon/Axios

Not insignificant if you also insert these charts in your bearish analysis:

The gap between the two PMI surveys is now the largest ever recorded. Historical evidence demonstrates the superiority of Markit’s data as regression analysis

reveal that since 2008 the IHS Markit index has exhibited a closer fit with the official data than the ISM has, the respective adjusted r-square values being 0.79 and 0.69. The regressions also indicate that the IHS Markit production index is running at a level consistent with an average 0.3% quarterly rate of decline in the fourth quarter while the ISM index is consistent with a 1.7% rate of quarterly decline. By comparison, the official data from the Fed so far in the fourth quarter are running 0.4% behind the third quarter despite the November rebound, which is clearly far closer to the IHS Markit signals than the much-weaker ISM survey.

Markit adds:

To help explain why the surveys differ we need to look closer at the methodologies:

- Survey panel sizes are different: IHS Markit’s survey panel is larger than the ISM’s stated panel size. IHS Markit surveys around 800 manufacturing companies (approximately double the size of the ISM panel size) from which an 80% response rate is typically received. However, unlike IHS Markit, ISM does not disclose actual numbers of questionnaires received. As a general rule, a large panel size produces more stable and accurate survey results, meaning the data tend to be less volatile and ‘noisy’.

- The surveys also use different panel structures: ISM data are based only on ISM members, and as such are likely to reflect business conditions in larger companies, with small- and medium-sized firms under-represented. In contrast, IHS Markit’s survey includes an appropriate mix of companies of all sizes (based on official data showing the true composition of manufacturing output each year).

- Survey responses may relate to different markets: The questionnaire that we have seen indicates that ISM does not specifically ask respondents to confine their reporting to US facilities/factories whereas IHS Markit specifies that all responses must relate only to business conditions at US factories. ISM data could therefore be more heavily influenced by global conditions facing of US-owned companies than the IHS Markit data. Note that global manufacturing growth outside of the US, as tracked by IHS Markit’s other PMI surveys, accelerated sharply in 2017, and has since matched the pattern of growth shown by the ISM. More recently, note that global-ex-US growth has slowed sharply to show some of the weakest rates seen over the past ten years.

That said, Boeing’s problems will likely impact a large swat of manufacturers in coming months:

Boeing Reassigns Staff as Spirit Eyes Furloughs Boeing will reassign as many as 3,000 workers that make the 737 MAX, and its biggest supplier is considering voluntary layoffs ahead of a planned production halt of the grounded jetliner.

(…) Boeing has said it will stop accepting MAX parts from suppliers later this month.

Farmers hoping for more “Trump money” in 2020

(…) Background: Farmers had a rough 2019, even with a hefty subsidy package provided to them by the Trump administration as relief from the trade war.

- Chapter 12 bankruptcies rose 24% over the previous year, and farm debt is projected to hit a record high $416 billion.

- Overall, farm income increased last year, but without the $14.5 billion tranche of farm subsidies delivered by the government, U.S. farm income would have fallen by about $5 billion from its already low 2018 level. (…)

What’s next: It’s unclear whether U.S. farmers will get more government aid in 2020, but experts say more farmers are becoming financially dependent on the subsidies, Beth Burger of the Columbus Dispatch wrote in November.

- “‘Trump money’ is what we call it,” Missouri farmer Robert Henry told NPR of the package that totaled $28 billion over two years. “It helped a lot.”

- “If the government doesn’t pay us, we’re done,†North Dakota farmer Justin Sherlock told Reuters last week.

The big picture: Many are unsure of what crops to plant because no specific details have yet been released on the deal, Reuters reported, noting that farmers in export-dependent regions say they can’t continue to sell their crops for below the cost of production without additional subsidies.

Between the lines: It’s hard to handicap the odds of a third round of farm subsidies because the Trump administration essentially pulled the money for the first two rounds “out of thin air,” NPR’s Dan Charles reported.

- “[The USDA] decided that an old law authorizing a USDA program called the Commodity Credit Corp. already gave it the authority to spend this money.”

The bottom line: The world’s agriculture supply chains have already changed and American farmers aren’t entirely sure where they fit or what products China will be buying.

- China has deepened ties with Brazil and Argentina, and its need for U.S. exports like soy and sorghum to feed livestock is waning because of a deadly pig disease experts estimate has killed about half the world’s largest hog herd.

-

US shopping mall vacancies hit two-decade high Proportion of empty units surpasses post-crisis peak as online shopping bites

-

Reis: Office Vacancy Rate unchanged in Q4 at 16.8%

Note how the office vacancy rate never really improved this cycle (chart from CalculatedRisk).

Eurozone inflation jumps but don’t get excited just yet Despite a strong increase in inflation and retail sales in December, it’s premature for hawks to get excited. This is not an environment in which core inflation pressures are increasing

The inflation rate jumped on energy price effects. As the oil price jumped in December and base effects played a role, headline inflation increased from 1 to 1.3%. Depending on oil price developments- which are likely to be volatile as Middle East tensions have spiked recently- it is expected that inflation could trend somewhat higher than the 1% range for the coming months. The real story though is in core inflation, which has been at 1.3% for two months in a row now. This is higher than expected and could encourage hawks at the European Central Bank to seek some clawback of the monetary stimulus provided in the second half of last year.

November’s retail sales numbers may also give rise to some excitement, coming in higher-than-expected at 1% month-on-month growth. It’s important to remember, however, that the rise of Black Friday across the eurozone will play an important role here.

Predictions for a sustained rise in core inflation still seem premature, as wage pressures have been moderating recently thanks to the sluggish and uncertain economic environment. The same holds for selling price expectations which have been trending down, indicating that more modest price growth is in the making in the months ahead.

While the higher core inflation reading will be on the ECB’s radar, continued sluggish growth and subsiding wage pressures make a quick rise to the 1.5-2% range an upside risk scenario, rather than a base case. Without material improvement in business confidence and the growth outlook, continued modest price growth seems the most likely scenario for the moment.

Narrative-fitted 2020 visions also impact earnings.

LARGER CUTS THAN AVERAGE TO S&P 500 EPS ESTIMATES FOR Q4

During the fourth quarter, analysts lowered earnings estimates for companies in the S&P 500 for the quarter. The Q4 bottom-up EPS estimate (which is an aggregation of the median EPS estimates for all the companies in the index) dropped by 4.7% (to $40.69 from $42.69) during this period.

During the past five years (20 quarters), the average decline in the bottom-up EPS estimate during a quarter has been 3.3%. During the past 10 years (40 quarters), the average decline in the bottom-up EPS estimate during a quarter has been 3.1%. During the past 15 years (60 quarters), the average decline in the bottom-up EPS estimate during a quarter has been 4.4%. Thus, the decline in the bottom-up EPS estimate recorded during the fourth quarter was larger than the five-year average, the 10-year average, and the 15-year average.

Insight/2020/01.2020/01.06.2020_TOW2/S&P%20500%20Change%20in%20Bottom%20Up%20EPS.png?resize=550%2C399&ssl=1)

As of today, the S&P 500 is expected to report a decline in earnings of -1.5% for the fourth quarter. Based on the average change in earnings growth due to companies reporting positive earnings surprises, it is likely the index will report earnings growth for Q4.

Over the past five years on average, actual earnings reported by S&P 500 companies have exceeded estimated earnings by 4.9%. During this same period, 72% of companies in the S&P 500 have reported actual EPS above the mean EPS estimate on average. As a result, from the end of the quarter through the end of the earnings season, the earnings growth rate has typically increased by 3.6 percentage points on average (over the past five years) due to the number and magnitude of positive earnings surprises.

If this average increase is applied to the estimated earnings decline at the end of Q4 (December 31) of -1.5%, the actual earnings growth rate for the quarter would be 2.1% (-1.5% + 3.6% = 2.1%).

If the index does report growth of 2.1% for Q4 2019, it will mark the first time the index has reported (year-over-year) earnings growth since Q4 2018.

Insight/2020/01.2020/01.03.2020_EI/S&P%20500%20Earnings%20Growth%20Est%20vs%20Actual.png?resize=550%2C399&ssl=1)

Bearish analysts tend to currently use Factset’s data to support the notion of a profit recession, now in its 4th quarter based on Factset’s numbers.

For its part, Capital IQ shows Q3’19 as the only negative quarter. And, should you be a purist using only “as reported†earnings, Q3’19 was also the only negative quarter and Q4 EPS will jump 26% YoY!

Refinitiv/IBES, which I prefer and use for its consistent common sense approach to P&L analysis, kept EPS growth positive in Q1 and Q2 of 2019.

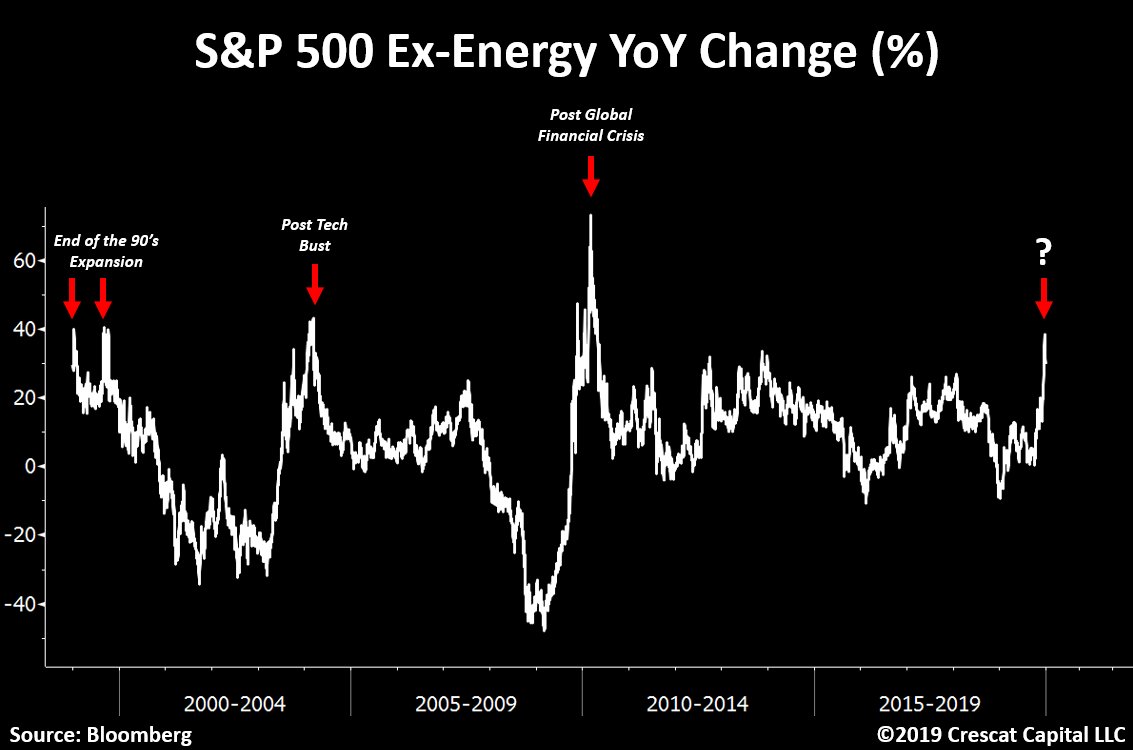

Interesting chart:

Tense Time for Buyers of Riskier Corporate Loans The lower reaches of the market for corporate loans have suffered sharp declines in recent months, a sign of growing aversion to earnings shortfalls or other strains at indebted companies including Murray Energy.

(…) In the U.S. at the start of December, some 2.5% of leveraged loans were trading at less than 70% of face value, the most since September 2016, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s LCD, the loan market research service.

Analysts and investors blame the loose credit standards that characterized the market in recent years, encouraged by strong demand from yield-hungry investors. The hunt for yield also fed a boom in new issuance of structured loan funds known as collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, which have been the biggest group of lenders in recent years.

But investors are shying away from such loans at any sign of trouble, including those deemed “covenant lite†for their scant investor protections, which is sparking steep falls in the prices of loans to firms—particularly when they fail to hit earnings targets. (…)

Another factor driving the selloff: many borrowers have been understating their leverage, or the amount of debt they have relative to earnings. They have done so by regularly inflating earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or Ebitda, by including forecasts for cost cuts or additional sales, according to investors, analysts and ratings firms. (…)

According to UBS data, average total debt on new deals is about 5.4 times Ebitda as presented by borrowers, but 6.7 times Ebitda once the add-backs are stripped out. “About 25% to 30% of outstanding leveraged loans are associated with deals done since 2017 that have add-backs worth about 25% of Ebitda,†Mr. Mish says.

S&P recently reviewed U.S. leveraged loans it rated in 2015 and 2016 to determine whether companies had fulfilled their projected earnings add-backs—and if leverage levels had fallen as expected. The finding was resoundingly negative.

Of new borrowers in 2016, more than 90% failed to hit earnings targets by the end of the second year of operation after they took out the loan. That meant debt remained a much higher multiple of earnings. Leverage at the median company was projected to fall to 3.1 times Ebitda by the end of the second year in S&P’s models based on management forecasts. In fact, it ended up at 5.9 times, the S&P study found. (…)

In a covenant-lite world, the natural reaction to any sign of stress is to sell out.

Huawei Gear ‘Top Notch,’ Says New CEO of Canadian Telco BCE

(…) Bibic’s comments come as the Canadian government faces a decision over whether to allow Huawei to play a bigger role in developing the 5G broadband network amid security concerns and as tensions between Canada and China remain stretched over the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou. (…)

Coincidentally,

Coincidentally,