U.S. Retail Sales Rose Briskly in October Americans spent briskly at retailers in recent months, supporting hopes for a strong holiday shopping season and giving the economy momentum.

Retail sales—measuring spending at restaurants, clothiers, online stores and other shops—rose 0.8% in October from the prior month, the Commerce Department said Tuesday. Sales grew 1% in September, revised figures showed, up from a previously reported 0.6% increase.

Those gains marked the best two-month stretch of sales in at least two years. (…)

Tuesday’s report showed that strong car sales accounted for much of the bounce in retail sales last month, as well as higher gasoline prices that drove up spending at service stations. But spending grew across a range of items, including construction materials, groceries and health care products. Excluding car purchases, sales rose 0.8%.

Meanwhile, Americans cut spending at furniture stores, department stores and restaurants. (…)

Retail sales have picked up more broadly—they rose 4.3% in the past 12 months, the best annual gain in almost two years—due to many factors lifting Americans’ confidence and discretionary income. (…)

Unseasonably warm weather also likely boosted retail traffic in October.

Two very strong months, across the board, following a weak August (table from Haver Analytics)

This will help that:

U.S. Business Inventories Inch Higher

Total business inventories increased 0.1% during September (0.6% y/y) following an unrevised 0.2% August gain. Total business sales improved 0.7%, and were up 0.8% y/y. The inventory-to-sales ratio eased to 1.38, down sharply from 1.41 during Q1.

New data in this report showed that retail inventories rose 0.2% (3.9% y/y) following a 0.6% increase, revised from a 0.7%. The gain was powered by a 0.7% surge (9.0% y/y) in motor vehicle inventories. Excluding autos, retail inventories were little changed (1.4% y/y).

California Ports See Delayed Import Surge as Hanjin Unwinds

(…) Container import volume at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which together handle the largest share of U.S. inbound trade in goods, expanded 7.1% and exports jumped 11.4%, according to the figures released by the port authorities.

The shipping volume marked a turnaround from a September in which the California ports reported fading import volume, including a 15% decline at Long Beach, as several Hanjin container ships sat offshore because the South Korean shipping line feared they would be seized by creditors after the company went into Korea’s version of bankruptcy protection in late August. (…)

O’Connell said that for September and October combined, the two ports handled nearly 1.4 million twenty-foot equivalent units, or TEUs, a common measure of shipping volume, just 0.6% ahead of the volume they saw in the same two-month period in 2015. (…)

Fed’s Bullard: Would be surprise if Fed didn’t hike rates in December

Most people would be.

U.S. Import prices resume decline

Inflation expectations have surged over the past week on the hope of massive fiscal stimulus in the United States. We believe that things have gone a little bit too far. For one, infrastructure spending is unlikely to be deployed before 2018. For another, the USD surged by the most in five years last week and is now virtually back to its cyclical peak on a trade-weighted basis. That will certainly have an impact on the short-term inflation outlook by depressing import prices.

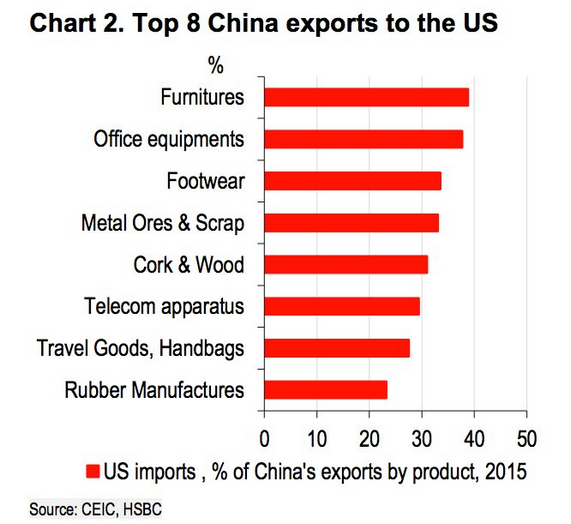

Data released earlier today showed non-fuel import prices (91.7% of U.S. merchandise imports) falling for the second consecutive month in October, the first such occurrence in eight months. Import price deflation is not over. As today’s Hot Chart shows, USDCNY fell to a new multi-year low this morning, a development that will continue to depress prices originating from the U.S. largest import trade partner (China accounts for 21.5% of total U.S. imports). So far this quarter, the CNY is already down more than 6% y/y vs. the USD, the biggest decline since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. (NBF)

From The Daily Shot:

What Surging Interest Rates Mean for Your Student and Auto Loans Mortgage rates have increased since Donald Trump was elected president—but that doesn’t mean consumers will immediately pay more for credit cards and other loans.

(…) Student and auto loans are more reliant on shorter-term measures, typically based on the London interbank offered rate, or Libor, or Treasury yields. The one-month Libor has barely budged since the election, while the three-month Libor is only up about 0.03 percentage point. So the costs of loans based on that shouldn’t jump in the same way as mortgages, which have now risen to slightly more than 4% on average for a 30-year, fixed-rate conforming loan.

And some consumer borrowing rates, say for credit cards and home-equity lines of credit, are influenced by the prime rate rather than instruments that trade daily. That rate is based on the Federal Reserve’s target for short-term rates. That currently stands at a range of 0.25% to 0.50%.

The bottom line for consumers: Interest rates for most loans aside from mortgages shouldn’t show big, immediate increases. Plus, these rates remain low by historical standards. (…)

It is true that Libor has barely bulged since the elections but it has been rising steadily throughout 2016. As to the prime rate, we shall hear about that in a month.

Meanwhile, mortgage apps to purchase are rolling over (CalculatedRisk):

Empire State Factory Sector Index Turns Positive

The Empire State Factory Index of General Business Conditions for November posted its first reading above zero since July. It rose to 1.5 from -6.8 in October. (…)

The new orders as well as the shipments readings both returned to positive territory following a few months of negative readings. Delivery times also slowed, but inventories fell more rapidly. The employment index declined. During the last ten years, there has been a 70% correlation between the index and the m/m change in factory sector payrolls. The average workweek figure was fairly stable m/m, but down sharply over the last three.

The prices paid index reversed improvement during the prior two months. Eighteen percent of respondents reported paying higher prices while three percent paid less. The index of prices received eased to 2.7. (…)

The Atlanta Fed’s GDP Now model finds itself way above the pack at +3.3% in Q4:

German economic growth halves in third quarter as exports decline

The German economy expanded 0.2% in the three months to September, according to results from official statistics body Destatis, indicating that growth has slowed markedly so far this year. In contrast, the economy grew 0.4% and 0.7% in the second and first quarters respectively. Moreover, the 0.2% growth rate was slightly below expectations of a 0.3% expansion and the weakest in a year. However, business surveys suggest growth is picking up again.

German economic growth and the PMI

Although no details were revealed, Destatis reported that the domestic market remained the mainstay of the German economy, with final consumption expenditure of both households and government continuing to increase and boost gross domestic product, while negative impulses came from trade.

The weakness in the GDP report had already been hinted at by business survey data, with the German PMI dropping to a 16-month low in September.

That said, the outlook for the fourth quarter looks positive, with business survey data such as the PMI and Ifo pointing to an acceleration in economic growth. (…)

Exports declined in the latest three-month period, while imports rose. Meanwhile, industry is likely to have had a mildly positive impact on economic growth. Industrial production expanded 0.2% in the three months to September, up substantially from a 0.8% decline in the second quarter.

In a separate report published last week, Destatis reported that Germany’s trade balance narrowed in September as exports fell 0.7%. Moreover, Germany’s economic ministry warnedthat German exporters are struggling amid global economic uncertainties stemming in part from the UK’s decision to leave the European Union and the surprise U.S. presidential election result.

The recent slump in the pound has made German goods and services less competitive in the UK (Germany’s second-largest single country trading partner) and it is therefore likely that the Brexit vote has had some negative impact on Germany’s trade balance in the third quarter. That said, the Manufacturing PMI New Export Orders Index reached its highest level since the beginning of 2014 in September and was little-changed in October, thereby suggesting that the weakness in the official data was only a temporary blip. (…)

The latest business survey results point to stronger economic growth at the start of the fourth quarter. The PMI recovered and reached its second-highest level this year so far in October, while Ifo’s Business Climate Index climbed to a two-and-a-half year high. Both IHS Markit and the German government expect GDP growth of 1.8% for 2016, which would be the strongest in five years.

Another Financial Warning Sign Is Flashing in China

The adjusted loan-to-deposit ratio, which includes a range of off-balance sheet items and is an indicator of the banking system’s ability to weather stress, climbed to 80 percent as of June 30, according to S&P Global Ratings. For some smaller lenders, the ratio has already topped 100 percent, S&P estimates.

S&P’s adjusted measure is rising much faster than the official loan-to-deposit ratio as banks pile into off-balance sheet lending, sidestepping government efforts to rein in credit. At the current pace, overall credit could surpass deposits on an adjusted basis within a few years — a level that would give China little leeway to stave off financial turmoil, S&P says.

“The next two to three years is a crucial window for China to rein in the ratio, or we will be in serious trouble,” said S&P’s Beijing-based director Liao Qiang. “Reaching 100 percent doesn’t mean a crisis will ensue immediately, but it shows China’s entire deposit base is used up and any loss of confidence from savers will severely destabilize the banking system.”

Even after S&P’s adjustments, the ratio in China remains lower than in many other countries. Yet the country’s rapid loan growth, diminishing return on credit and rising bad debts combine to make deposits a particularly important buffer against future financial distress, according to Liao. (…)

OPEC, Russia Expand Diplomatic Push to Secure Oil-Cuts Deal

![]() Please, read this note from Ray Dalio (the entire piece is even better):

Please, read this note from Ray Dalio (the entire piece is even better):

Reflections on the Trump Presidency, One Week after the Election

(…) we chose not to bet on whether or not he would be elected and/or whether or not he would be prudent because we didn’t have an edge in predicting these things. We try to improve our odds of being right by knowing when not to bet, which was the case.

Having said that, we want to be clear that we think that the man’s policies will have a big impact on the world.(…) What follows are simply our preliminary impressions from these. (…)

Donald Trump is moving forcefully to policies that put the stimulation of traditional domestic manufacturing above all else, that are far more pro-business, that are much more protectionist, etc. (…) As a result, whereas the previous period was characterized by 1) increasing globalization, free trade, and global connectedness, 2) relatively innocuous fiscal policies, and 3) sluggish domestic growth, low inflation, and falling bond yields, the new period is more likely to be characterized by 1) decreasing globalization, free trade, and global connectedness, 2) aggressively stimulative fiscal policies, and 3) increased US growth, higher inflation, and rising bond yields.

(…) the main point we’re trying to convey is that there is a good chance that we are at one of those major reversals that last a decade (like the 1970-71 shift from the 1960s period of non-inflationary growth to the 1970s decade of stagflation, or the 1980s shift to disinflationary strong growth). To be clear, we are not saying that the future will be like any of these mentioned prior periods; we are just saying that there’s a good chance that the economy/market will shift from what we have gotten used to and what we will experience over the next many years will be very different from that.

To give you a sense of this, the table below shows that a) these economic environments tend to go on for about a decade or so before reversing, b) market moves reflect these environments, and c) extended periods of movements in one direction (which lead to confidence and complacency) tend to lead to big moves in the opposite direction.

As for the effects of this particular ideological/environmental shift, we think that there’s a significant likelihood that we have made the 30-year top in bond prices. We probably have made both the secular low in inflation and the secular low in bond yields relative to inflation. (…)

Because the effective durations of bonds have lengthened, price movements will be big. Also, it’s likely that the Fed (and possibly other central banks) will increasingly tighten and that fiscal and monetary policy will come into conflict down the road. Relatively stronger US growth and relative tightening of US policy versus the rest of world is dollar-bullish. All this, plus fiscal stimulus that will translate to additional economic growth, corporate tax changes, and less regulation will on the margin be good for profitability and stocks, though for domestically oriented stocks more than multinationals, etc.

The question will be when will this move short-circuit itself—i.e., when will the rise in nominal (and, more importantly, real) bond yields and risk premiums start hurting other asset prices. That will depend on a number of things, most importantly how the rise in inflation and growth will be accommodated, that we don’t want to delve into now as that would take us off track. (…)

Our very preliminary assessment is that on the economic front, the developments are broadly positive—the straws in the wind suggest that many of the people under consideration have a sufficient understanding of how the economic machine works to run reasonable calculations on the implications of their shifts so that they probably won’t recklessly and stupidly drive the economy into a ditch. To repeat, that is our very preliminary read of the situation, which is too premature to take to the bank. Of course, we should expect big bumps resulting from big shifts regardless of who is engineering this big ideological shift.

So, what are we trying to say? The headline is that the ideological/environmental shifts are clear, their magnitudes will be large, and there’s a good chance that the “craziness” factor will be smaller and play a lesser role in driving outcomes than many had feared. In fact, it is possible that we might have very capable policy makers of the previously mentioned ideological persuasion in control. As always, we will keep you posted of our thinking as it will certainly change as we learn more.