Bank of England Outpaces Peers With Rate Rise of Half Percentage Point Lending rate rises to highest level [5%] since April 2008

(…) Norway’s central bank also increased its core lending rate by half a percentage point Thursday, while Switzerland hiked its benchmark rate by a quarter point. Both warned of further increases in the coming months.

The European Central Bank, the Bank of Canada and the Reserve Bank of Australia have all raised rates by a quarter percentage point in recent weeks. The Federal Reserve kept its key rate unchanged but also signaled it isn’t done raising rates. (…)

Policy Error?

Source: BCA Research via The Daily Shot

Three Uncomfortable Truths For Monetary Policy (IMF)

Excerpts from Gita Gopinath’s yesterday speech at the European Central Bank’s annual conference. You can jump to the last paragraph for the clear message.

(…) Uncomfortable Truth #1: Inflation is taking too long to get back to target.

Inflation forecasters have been optimistic that inflation will revert quickly to target ever since it spiked two years ago. (…) inflation sits well above previous forecasts. (…)

Despite repeated forecast errors, markets remain particularly optimistic that inflation in the euro area and most advanced economies will recede to near-target levels relatively quickly.These disinflation hopes—likely fueled by the sharp drop in energy prices—underpin expectations that policy rates will decline soon, despite central bank guidance to the contrary. Surveys of market analysts paint a similar picture and suggest that inflation is likely to come down without much of a hit to growth. It is useful to bear in mind that there is not much historical precedent for such an outcome.

Setting aside forecasts, the fact is that inflation is too high and remains broad-based in the euro area, as in many other countries. While headline inflation has eased significantly, inflation in services has stayed high, and the date by when it is expected to return to target could slip further. (…)

The combination of tight labor markets with a still solid stock of household savings and residual pent-up demand may be behind the resilience in activity we have seen so far.

Second, despite the large increase in the nominal policy rate, financial conditions may not be tight enough which impedes monetary policy transmission. (…) real rates using market-based measures of inflation expectations are still quite low, and near-term real rates using household measures are likely negative.

Lastly, the pandemic has likely lowered potential output and productivity, which would also help explain some of the upward pressure on inflation.

What is worrisome is that sustained high inflation could change inflation dynamics and make the task of bringing inflation down more difficult. Given the massive decline in real wages since the pandemic, some wage catchup is to be expected. All else equal, if inflation is to fall quickly, firms must allow their profit margins—which have shot up during the past two years—to decline and absorb some of the expected rise in labor costs. But firms may resist this, especially if the economy remains resilient, while workers may demand payback for their real wage losses. Such dynamics would slow inflation reduction and likely feed into expectations and increase susceptibility to further upside cost or resource pressures. (…)

Ultimately, it is up to central banks to deliver price stability irrespective of fiscal stance. With underlying inflation high and upside inflation risks substantial, risk management considerations in the euro area suggest that monetary policy should continue to tighten and then remain in restrictive territory until core inflation is on a clear downward path.

The ECB—and other central banks in a similar situation—should be prepared to react forcefully to further upside inflation pressures, or to evidence that inflation is more persistent, even if it means much more labor market cooling. The costs of fighting inflation will be significantly larger if a protracted period of high inflation boosts inflation expectations and changes inflation dynamics.

There are also some downside risks to inflation that could arise, for instance, from the recent unwinding of supply chain disruptions and fall in energy prices. The effect of the recent tightening in monetary policy is still working through the system. While central banks must be vigilant about not easing prematurely, they should be prepared to adjust course if a chorus of indicators suggest that these downside inflation risks are materializing.

Uncomfortable Truth #2: Financial stresses could generate tensions between central banks’ price and financial stability objectives.

If inflation persists and central banks need to tighten much more than markets expect, today’s modestly tight financial conditions could give way to a rapid repricing of assets and a sharp rise in credit spreads. We’ve seen during the past year how, under some circumstances, policy tightening can come with significant financial stresses, including in Korea, the UK, and more recently in the US.

For the euro area, tighter monetary policy may also have diverse regional effects, with spreads rising more in some high-debt economies. Higher rates can also amplify other vulnerabilities arising from household indebtedness and a large share of variable rate mortgages in some countries.

This brings me to the second uncomfortable truth:, Financial stresses could generate tensions between central banks’ price and financial stability objectives. This is because, while central banks can extend broad-based liquidity support to solvent banks, they are not equipped to deal with the problems of insolvent borrowers. (…)

While central banks must never lose sight of their commitment to price stability, they could tolerate a somewhat slower return to the inflation target to avert systemic stress. (…)

Such a shift in the reaction function could leave the central bank behind the curve in fighting inflation – as, for instance, happened when the Federal Reserve decided to ease policy in the mid-1960s on fears of a credit crunch, even as inflation pressures were building.

Put simply, while separation is achievable in principle, it is challenging in practice, and must not be taken for granted. (…)

Uncomfortable Truth #3: Central banks are likely to experience more upside inflation risks than before the pandemic.

(…)

Looking forward, central banks are likely to experience more upside inflation risks than before the pandemic for two sets of reasons. Some of the upside risk reflects structural changes affecting aggregate supply—heightened by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine—and that may result in larger and more persistent shocks. In addition, we have also learned the lesson that the Phillips Curve is not reliably flat.Turning first to structural changes, there is a substantial risk that the more volatile supply shocks of the pandemic era will persist. Despite a considerable easing of pandemic-related supply pressures, the restructuring of global supply chains that was intensified by the pandemic and war, coupled with geo-economic fragmentation, may cause ongoing disruptions to global supply.

Many countries are turning to inward-looking policies, which raise production costs, and, ironically, make countries less resilient and more susceptible to supply-side shocks (WEO, April 2022). (…) the number of new restrictions on trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) imposed on EU countries ratcheted up markedly during the pandemic. EU countries have also increased their own restrictions on in-bound trade and FDI.

The increasing physical and transition risks from climate change are also likely to amplify short-term fluctuations in inflation and output. Delays in achieving Paris Agreement goals increase the risk of a disorderly transition and serious disruptions to energy supply, which could boost inflation sharply and create more difficult tradeoffs for central banks.

The pandemic has also taught us more about the Phillips Curve. Evidence increasingly shows that nonlinearities may become pronounced at high levels of resource utilization, so that inflation is more sensitive to resource pressures. Difficulties in measuring economic slack may also make it harder for policymakers to gauge the point at which inflationary pressures will escalate.

(…) Central banks may need to react more aggressively if the supply shocks are broad-based and affect key sectors of the economy, or if inflation has already been running above target, so that expectations are more likely to be dislodged. They may also need to react more aggressively in a strong economy in which producers can pass on cost hikes more easily and workers are less willing to accept real wage declines. And they should be confident that the shocks are mainly supply-driven, rather than fueled by strong demand.

While the focus now is on high inflation, what we’ve learned about the Phillips Curve also has important implications for the monetary policy response to future periods of below-target inflation. Some refinement may be needed to the “lower-for-longer” strategies—used widely after the Global Financial crisis—that typically involved maintaining policy rates at the effective lower bound until inflation reaches or overshoots its target. Lower-for-longer strategies may still be desirable under some conditions, particularly for an economy in deep recession and facing chronically low inflation.

But the pandemic experience suggests that policymakers should be more cautious about calibrating policy to generate a persistent fall of unemployment below the natural rate U* when inflation is running only modestly below target—say between 1.5 percent and 2 percent. And there could well be a case for preemptive tightening under these conditions if resource pressures appear tight and there is a material risk that new shocks—such as fiscal expansion—could push the economy to overheat.

By allowing for a more gradual pace of tightening, a preemptive approach would also reduce the financial stability risks likely to accompany a rapid exit from low rates (the second uncomfortable truth).

Refining monetary policy strategies also calls for adjusting the use of tool. Forward guidance is a helpful tool, and conditional promises can enhance its impact. But such promises should be tempered by escape clauses if developments unfold much differently than expected. The forward guidance provided by central banks during the pandemic may have been too much of a straitjacket and prevented a faster reaction to inflation surprises.

The costs and benefits of quantitative easing (QE) should also be reconsidered. QE will likely remain a critical tool should central banks face circumstances like the post-GFC period in which unemployment runs high and inflation low even though policy rates have hit their floor. But there should be more wariness of using QE—and accompanying it with forward guidance promising low policy rates—when employment has largely recovered, and inflation remains only modestly below target. Maintaining QE in such circumstances increases the risk that the economy will overheat and that policy will be forced into a sharp U-turn.

So, when we consider the monetary policy of tomorrow, it is important to recall today’s lessons: First, take a closer look at supply shocks before deciding to simply “look through” them. Second, be careful about running the economy hot, and be ready to act preemptively if it does—even if inflation isn’t yet burning brightly. Third, make sure that forward guidance is coupled with escape clauses; and fourth, be more cautious about deploying QE outside of a recession.

To conclude, now is the time to face the three uncomfortable truths that I’ve outlined. Inflation remains sticky; financial stresses could make price and financial stability a difficult balancing act; and more upside inflation risks will likely come our way. I am heartened by the actions that the ECB—and many other central banks—have taken to tackle inflation. But the battle won’t be easy—financial stresses may intensify, and growth may have to slow more. Even so, we know that we can’t have sustained economic growth without a return to price stability. The good news is that while low inflation may seem elusive, it is certainly no stranger, and central bank actions can deliver it. Unlike the characters in Godot, we are not waiting for a potential stranger to arrive; we are inviting an old friend to return.

Not waiting for Godot, fixed income investors are already in risk management mode as Almost Daily Grant’s reports:

Full faith in credit? Nearly two-thirds of this year’s junk bond supply has been backed by specific collateral, PitchBook-tabulated data from last week show. That’s far and away the highest proportion since at least 2005, surpassing the 37% share seen in 2009 following the acute phase of the financial crisis. With post-pandemic policy tightening pushing benchmark borrowing costs to decade-plus long heights, investors “want to be a little more defensive in an uncertain environment, so they’re buying this secured paper,” Randy Parrish, head of public credit at Voya Investment Management, commented to The Wall Street Journal.

Risk aversion is similarly on display in the floating-rate realm. Issuance of syndicated leveraged loans registered at just $31.3 billion from January through May, marking the weakest primary activity since 2009, when the loan market stood at less than half of its current $1.4 trillion size.

Underscoring the changing market dynamics: only a solitary single-B-minus rated loan backing a leveraged buyout has priced in 2023, compared to 14 such issues in the same period last year. That comes as the share of single-B-minus issues within the Morningstar LSTA Leveraged Loan Index has ballooned to nearly 30% from 14% on the eve of the pandemic. Meanwhile, borrowers looking to refinance are paying a pretty penny to do so, with the market-wide 9.68% average effective yield representing the highest since Y2K.

Accordingly, it is perhaps no surprise that fewer than 13% of loans outstanding in the Morningstar gauge in April 2022 had been repaid 12 months later, half of the ratio seen last year and the lowest such share since 2009. The raft of aging vintages may portend building distress, PitchBook notes, as loans have historically defaulted at a 1.4% rate within one year of origination but at a 5.4% clip by year four.

(…) UBS strategist Matthew Mish wrote Wednesday that he anticipates private credit defaults will reach as high as 10% early next year, compared to 8% and 6% for leveraged loans and junk bonds, respectively, as the impact of higher rates takes hold within the opaque asset class (the Proskauer Private Credit Default Index reached 2.15% in the first quarter, up from 1% in the last three months of 2021). A recession-induced easing cycle could help bring private credit defaults to 5% by late 2024, Mish reckons, though “if rates stay higher for longer and ultimately lead to a less mild recession, we could see a longer cumulative default scenario.”

Analysts at Moody’s express similar concern, warning on Friday that private credit now faces its “first serious challenge.” Loan vintages from the euphoric 2021 era, “when optimism was high, the credit market was most frothy and there was greater tolerance for looser covenants,” could prove particularly problematic, the rating agency believes, as its in-house liquidity stress indicator has risen markedly from a year ago. Lenders can likewise expect lower recovery rates in the case of future defaults, owing to the steady erosion of covenant strength during the lengthy post-crisis bull market.

FYI:

- Almost half of market participants in a Bloomberg survey expect at least two more rate hikes. That’s a remarkable shift for a market that was pricing in cuts in 2023 as recently as this month.

- A soft landing now appears elusive, though the US may be stuck in a pre-recession limbo for the rest of the year. That’s probably why many investors see fixed-income outperforming commodities and stocks. (Bloomberg)

- Ford plans to fire hundreds of salaried US workers—mostly engineers—this week, people familiar said.

- Goldman Sachs has started cutting managing directors across its global operations as part of a cost saving drive amid a dealmaking slump. It’s slashing around 125 positions, including some in investment banking, after deal values fell more than 40% this year to $1.2 trillion. These cuts follow reports of similar cost saving exercises at other banks. JPMorgan cut around 40 investment bankers, according to reports last week, while Citigroup is planning hundreds of cuts across the company this year.

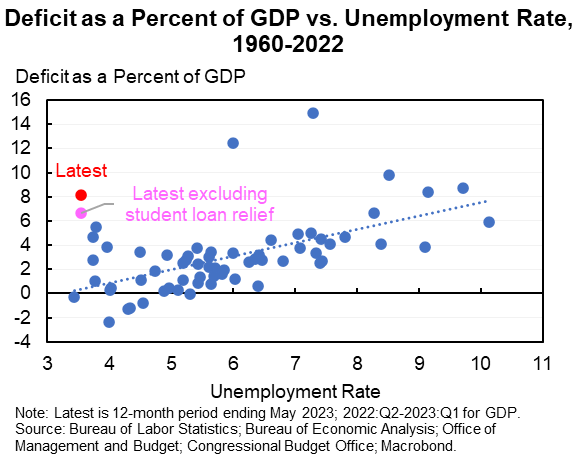

- Over the last 12 months the budget deficit has been 8% of GDP (6% ex student loans) while the unemployment rate has averaged 3.6%. Historically this low an unemployment rate is associated with a balanced budget. @jasonfurman

TECHNICALS WATCH

It has now been more than three months since the S&P 500 has pulled back at least 3%, one of the longest such stretches since World War II, Deutsche Bank research shows. The average weekly move for the benchmark has been less than 1% in either direction since the end of March, according to FactSet. In late 2022, the index averaged swings of roughly 2.6% each week.

Others say technical dynamics in the stock and options market have pushed volatility lower. One measure of how tightly stocks within the S&P 500 are moving together, known as correlation, has fallen to some of the lowest levels on record in the past three months, according to Deutsche Bank, a sign that stocks and sectors are moving in dramatically different directions.

This “has been a key driver of lower index [volatility] and suggests a decline in the pricing of macro concerns,” the firm’s analysts wrote in a recent note to clients.

Correlations within stocks haven’t been this low since late 2017 and early 2018, around the time a burst of volatility known as “Volmageddon” jolted markets. If stocks across the S&P 500 start moving in lockstep once again, that would drive volatility higher. (…) (WSJ)