RECESSION WATCH

U.S. Labor Market Conditions Index Falls to New Low

The Labor Market Conditions Index from the Federal Reserve Board includes 19 indicators of labor market activity, covering the broad categories of unemployment and underemployment. These include jobs, workweeks, wages, vacancies, hiring, layoffs, quits and surveys of consumers and businesses. Because the trends in the index are slow-moving, Haver presents only the changes in the index. All are measured monthly and have been seasonally adjusted.

During February, the index deteriorated to the greatest degree since June 2009, the last month of the recession. Last month’s weakening runs counter to the improvement in payroll employment reported Friday, because it also reflects other weaker indicators in the report, including the stable unemployment rate, the decline in hours worked, the drop in average hourly earnings and the rise in the average duration of unemployment. During all of last year, the index rose moderately following a stronger performance in 2014. During the last ten years, there has been an 85% correlation between the change in the index and m/m growth in nonfarm payrolls.

Doug Short gives us more about this new indicator:

The indicator, designed to illustrate expansion and contraction of labor market conditions, was initially announced in May 2014, but the data series was constructed back to August 1976. Here is a linear view of the complete LMCI. We’ve highlighted recessions with callouts for its value the month recessions begin and for the latest index value.

As we readily see, with the exception of the second half of the double-dip recession in the early 1980, sustained contractions in this indicator is a rather long leading indicator for recessions. It is more useful as a general gauge of employment health. Note that in the most recent FOMC minutes for January 26-27, the phrase “labor market conditions” was used nine times. Maximum employment, after all, is one of the Fed’s twin mandates.

Interestingly enough, the FEDS Notes article announcing the indicator doesn’t chart the complete series with monthly granularity. Instead, the authors use a column chart to show blocks of six-month averages for the two halves of each calendar year since 1977. This approach further supports the use of the indicator as a general gauge of health. Here is our larger version of the same graphic model.

We couldn’t resist the urge to create a chart of the more conventional six-month moving average of the indicator. Note that we’ve adjusted the vertical axis to capture the depth of the contraction during the last recession.

Looks like the FOMC won’t get too giddy after last week’s employment report. Doug’s charts are good stuff for recession callers. At a minimum, the LMCI supports Lael Brainard’s call for “risk-management” (see below). But what about inflation, the other Fed mandate? Drew sent me a link to Kessler’s blog which argues that the recent inflation flare is only normal in the context of a business cycle.

The typical business-cycle sequence is that the manufacturing sector weakens first, then employment and consumer spending, and lastly, inflation. In fact, it is often not until the recession is over that inflation begins to come down. Inflation is the longest lagging indicator.

In fact, most past recessions were actually caused by the Fed precisely to kill inflation so there is no surprise that inflation would peak after recessions began. Kessler’s point is really to reinforce its view that “we have entered or will soon enter a full blown US recession”.

As we have pointed out here and here, manufacturing has clearly turned down in a way (3 independent indicators) that has not failed in calling an upcoming recession.

It is tempting to say that Kessler, “Specialists in US Treasuries”, are talking their book. Yet, they do serious research:

We know that the U.S. manufacturing industry is in recession. We also know that it now represents a much smaller percentage of the economy which might tempt us to dismiss its contraction. Yet, we should also understand that an important part of the service economy is dependant on manufacturers’ activity. Ask retailers, bankers, accountants etc. in Houston, Oklahoma or North Dakota.

While a lot of economists and investors have been comforted by the bedtime story of a puny and unimportant manufacturing sector, that story has been nothing but a misleading fractured fairy tale. Manufacturing is an important sector and while its employment share is low, goods drive a lot of activity and the sector is much more important than just its employment share. There is a new piece of research (here) from the MAPI Foundation that uses input-output analysis to show the fully integrated impact of the manufacturing sector in the context of the U.S. economy. The report (…) goes on to look at the full output and employment effects of bringing a manufacturing dollar’s-worth of product to market. It finds a surprising substantial impact

Viewed in this way, the U.S. manufacturing footprint and multiplier rise sharply. It is still not fair to call these effects either `manufacturing’ jobs or spending (they might be in some cases), but it is fair to call it a broader manufacturing sector impact. And this report helps to explain why the tiny-seeming manufacturing David is felling the service sector Goliath. (Robert Brusca)

This may explain the recent surprise drop in the U.S. Services PMIs with Markit’s falling into contraction territory and the ISM Services employment index declining sharply to 49.7 in February.

Markit digs further:

Markit’s manufacturing and services PMIs collectively showed the economy grinding to a halt in February, as signalled by a composite Output Index reading of 50.0. This was its lowest level since the financial crisis with the sole exception of October 2013, when the government shutdown disrupted business.

The more detailed sector data revealed how three out of the seven monitored sectors – healthcare, technology and industrials – slipped into decline in February, the most since the series began in October 2009. In January, only one sector – consumer services – had been in decline, and that in part reflected adverse weather.

While the remaining sectors noted growth of activity, the respective rates of expansion were modest at best.

A survey-record decline in output meant that healthcare was bottom-ranked in February. Underlying data showed that the downturn was driven by a first reduction in new orders since the series began almost six-and-a-half years ago.

The next two worst-performing sectors were technology and industrials, where output fell for the first time in 28 and 41 months respectively.

Growth of new business was relatively subdued in both cases. Despite slower growth of output, companies based in healthcare, technology and industrials continued to raise employment, pointing to lower productivity.

Meanwhile, consumer goods and financials had been the two best-performing groups in January, but marked slowdowns in output growth saw them slip to third and fourth place respectively. In particular, financial services activity rose at the weakest pace in over three years amid a near-stagnation in new work.

Data were slightly brighter for consumer services and basic materials. The modest rise in consumer services activity was enough for the sector to climb to the top of the rankings, though this was in part likely to have reflected a temporary rebound after severe weather disrupted the leisure sector in many states in late January.

Hmmm…can’t wait to see the March employment report. Meanwhile, the cheerleaders keep hopping (or hoping…):

-

Economists brush off downturn fears US is recovering and low oil prices good for growth, report says

(…) In a call for a “reality check”, Olivier Blanchard, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, and his colleagues at the Peterson Institute of International Economics say that global economic pessimism in 2016 has been in contravention of basic economic facts. (…)

While there were challenges across the world, notably from slow productivity growth, “most of the major economies, starting with China and the US, are growing more sustainably now than a decade ago, at their slower rates”, he said. “All the more reason then not to allow ourselves to be distracted by a financial market tail wagging the macroeconomic dog.”

The report notes that despite low oil prices hitting investment in energy projects in the US, jobs growth in the country is strong, as are real income growth and household spending.

Though Chinese growth was slowing, consumption was also rising strongly and the overhang of unsold property was getting smaller, raising hopes that the Chinese authorities could use the time to restructure over-indebted state-owned enterprises often in the heavy industrial sector. (…)

U.S. Consumer Borrowing Slows Amid Market Turmoil Borrowing by U.S. consumers slowed at the start of the new year, a possible sign of caution among households at a time of volatility in global financial markets.

Outstanding consumer credit, a measure of non-real estate debt, rose by a seasonally adjusted $10.54 billion in January from the prior month, the Federal Reserve said Monday. The 3.58% seasonally adjusted annual growth rate was the slowest growth pace since March 2013; in dollar terms, it was the smallest increase since November 2013. (…)

Consumer credit rose at a 7.28% pace in December, revised up slightly from an earlier estimate.

Revolving credit outstanding, mostly credit cards, decreased at a 1.35% annual pace in January compared with growth at a 7.05% pace in December. It was the first monthly decline for revolving credit since February 2015.

Nonrevolving credit outstanding, including student and auto loans, increased at a 5.36% annual pace in January compared with December’s 7.36% growth rate. (…)

Haver Analytics has another viewpoint: U.S. Consumer Credit Usage Increases

Consumer credit outstanding increased $10.5 billion during January (6.5% y/y) following a $6.4 billion December rise, revised from $21.3 billion. Action Economics Forecast Survey participants looked for a $17.0 billion January increase. During the last ten years, there has been a 46% correlation between the y/y growth in consumer credit and y/y growth in personal consumption expenditures.

Nonrevolving credit borrowing grew $11.6 billion (6.9% y/y) after a $0.9 billion increase, changed from $15.4 billion reported last month. Revolving consumer credit in January fell $1.1 billion (+5.3% y/y) following a little-revised $5.5 billion gain.

Now Coming to the Commercial Property Market: Defaults

(…) New signs of weakness are surfacing in the commercial property market, ending a half-decade run of improvement with steadily climbing values. Amid global shifts like the sluggish Chinese economy and a new era of low oil prices, defaults on loans are popping up in areas that were considered overheated, occurring in small numbers for now, but stoking fears that more could be on the way. (…)

“We’re at the top of the market,” said Kenneth Riggs, president of Situs RERC, a real-estate research firm that advises investors on property values and market direction. “There’s going to be a market correction.” (…)

Meanwhile, loans are becoming harder to secure even for safe investments such as well-leased buildings. That is because broader market volatility has caused lenders who sell off their loans via bonds known as commercial mortgage-backed securities to grow wary. While the segment made about $100 billion in loans last year, it has grown to a virtual halt today, lending executives said. If that continues, it will become more difficult for landlords who took out 10-year loans in 2006 to refinance today. (…)

Fed’s Fischer sees ‘first stirrings’ of rising inflation

(…) In a speech to a group of business economists in Washington on Monday, Stanley Fischer, the Fed’s vice-chairman, dismissed critics within the profession who have pointed to wage stagnation in the US as evidence that the traditional link between strong employment and inflation “must have been broken”.

“I don’t believe that. Rather the link has never been very strong, but it exists, and we may well at present be seeing the first stirrings of an increase in the inflation rate — something that we would like to happen,” he told the National Association of Business Economists. (…)

Speaking across town to a group of bankers on Monday, Lael Brainard, a member of the Fed’s board of governors who has emerged in recent weeks as one of its most vocal doves, said the Fed still needed to be mindful of “weak and decelerating foreign demand”. It meant policymakers should not take “the strength in the US labour market and consumption for granted”, she said.

“Tighter financial conditions and softer inflation expectations may pose risks to the downside for inflation and domestic activity,” she said. “From a risk-management perspective, this argues for patience as the outlook becomes clearer.”

She also warned that the FOMC “should put a high premium on clear evidence that inflation is moving toward our 2 per cent target” and that “inflation has persistently underperformed relative to our target”. (…)

China’s Exports Tumble Amid Broad Slowdown

China’s customs administration reported Tuesday that exports fell 25.4% in dollar terms year-over-year last month, compared with a drop of 11.2% in January. Though last month’s long Lunar New Year holiday contributed to the decline, the figure was much worse than a median forecast for a 15% slide by 17 economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal.

Imports also declined, falling 13.8% last month, the agency reported, compared with an 18.8% drop in January, in a further cooling of demand in China that is affecting its Asian neighbors. China’s trade surplus narrowed in February to $32.59 billion from $63.29billion in January, falling short of the median forecast of a $51.25 billion surplus. (…)

The poor export showing dovetails with trade results from other major exporters in the region. Last month, Taiwan’s exports fell for the 13th straight month—the island’s longest export slump since the global financial crisis—while South Korean exports declined for the 14th consecutive month. China’s February results were the weakest since May 2009, when exports fell 26.4%. (…)

Many blame the calendar quirks but this is a lower low (chart from Bloomberg)

German Industrial Production Surges by Most Since 2009

Production, adjusted for seasonal swings, climbed 3.3 percent from the prior month after retreating a revised 0.3 percent in December, data from the Economy Ministry in Berlin showed on Tuesday. That’s the biggest increase since September 2009 and the first gain in three months. It was stronger than all projections in a Bloomberg survey of economists, which had a median forecast for 0.5 percent growth. (…)

Construction jumped 7 percent from December and investment goods output rose 5.3 percent, the report showed. Consumer goods production increased 3.7 percent and manufacturing increased 3.2 percent. Industrial output rose 2.2 percent from a year earlier, again beating the highest economist estimate. (…)

German Orders Erode in January on Domestic Weakness

German Orders Erode in January on Domestic Weakness

German orders fell in January for the second straight month. However, each month the declines were relatively small, and together, they fail to offset the 1.5% order gain in November so that the three-month change is still positive. Over three months orders are up at a 4.8% pace, up from 2.4% over six months which also was up from 1% over 12 months. Orders are expanding and accelerating sequentially despite the two-month drop.

German orders are fighting two opposite trends. Foreign orders are accelerating sharply sequentially while domestic orders are weakening sequentially. So far, foreign order strength is dominating the trend based on stronger shorter term rates of growth. However, year-over-year, the growth in foreign and domestic orders is nearly identical at about 1% (i.e., 1.2% foreign; 0.8% domestic). The year-over-year growth rate in foreign orders has just turned positive. (…)

Capital goods trends are decelerating, showing sales dropping over three months and over six months. Other sectors show both growth and acceleration. Normally the preponderance of strength would simply make that the end of the story. But for Germany, capital goods tend to be at the core of its strength so the progressive weakness and deceleration there gives me pause. (…)

Oil edges lower after Kuwait dents hopes for output freeze

(…) Kuwait’s oil minister said on Tuesday that his country’s participation in an output freeze would require all major oil producers, including Iran, to be on board.

“I’ll go full power if there’s no agreement. Every barrel I produce I’ll sell,” Anas al-Saleh told reporters in Kuwait City.

OPEC member Kuwait is currently producing 3 million barrels of oil per day, he added.

On Monday the Ecuadorean government said that Latin American oil producers would meet on Friday to coordinate a strategy to halt the crude price rout.

Tuesday’s report by Goldman Sachs said that a recent surge in commodity prices was premature and unsustainable. (…)

Long-term Japanese bonds set record lows 30-year bond yield falls 22.2bp in single trading session

(…) The benchmark 10-year JGB yield fell below zero in mid-February and was quoted at -0.11 basis points on Tuesday. Last week, Japan sold a new 10-year bond at a negative yield for the first time, meaning that buyers are effectively paying the country for lending it money over a decade.

Bonds needing to be repaid in seven years now carry a yield of minus -0.23 per cent.

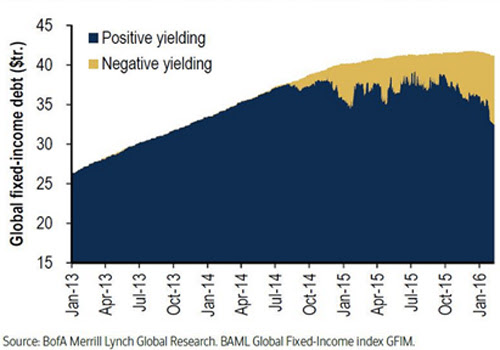

This is truly amazing: (via Tony Sagami)