U.S. Leading Economic Indicators Gain Is Steady & Firm

The Conference Board’s Composite Index of Leading Economic Indicators increased 0.6% (3.1% y/y) during February, the same as during the prior two months.

A steeper interest rate yield curve had the largest positive effect on the leading index, along with a higher ISM new orders index. Fewer initial claims for unemployment insurance followed along with higher stock prices. Improved consumer expectations for business/economic conditions and the leading credit index also added to the index’s gain, but fewer building permits contributed negatively.

From the Conference Board:

In the six-month period ending February 2017, the leading economic index increased 2.3 percent (about a 4.6 percent annual rate), much faster than the growth of 0.8 percent (about a 1.6 percent annual rate) during the previous six months. In addition, the strengths among all ten leading indicators have become very widespread.

And these great charts from Doug Short. No recession in sight:

HARD DATA WATCH

U.S. Industrial Production Steady in February U.S. industrial production was flat in February, though underlying figures suggest steady economic growth amid a pickup in manufacturing and mining activity.

(…) Output for January fell a revised 0.1% instead of an initially estimated 0.3% drop.

Overall industrial production was held in check by warmer-than-usual weather, which depressed demand at utilities, the Fed said. Elsewhere, the report was broadly positive. (…)

Manufacturing output, the biggest component of industrial production, climbed 0.5% in February to reach its highest level since July 2008. (…)

Capacity use, a measure of slack in the economy, decreased 0.1 percentage point to 75.4%, in line with economist expectations. Capacity use remains well below the long-run average of 79.9%, a sign the economy is operating below its potential.

Manufacturing is finally showing steady positive numbers even though the consumer side remains spotty (table from Haver Analytics):

![]() But in reality, the recent strong PMIs seem to be right after all. Revisions to January data reveal that total manufacturing output rose 0.5%, not +0.2% as originally reported, with strong upward revisions in Consumer Goods (-0.1% vs –0.8%) and Construction Supplies (+1.4% vs +0.9%).

But in reality, the recent strong PMIs seem to be right after all. Revisions to January data reveal that total manufacturing output rose 0.5%, not +0.2% as originally reported, with strong upward revisions in Consumer Goods (-0.1% vs –0.8%) and Construction Supplies (+1.4% vs +0.9%).

At the end of January, manufacturing output looked to have grown at a 1.6% annualized rate over the previous 3 months with Consumer Goods at –1.2%, Business Equipment at +1.6% and Construction Supplies at +4.9%. After the revisions and the rather strong February numbers, the past 3 months are now +4.9% annualized for total manufacturing, +2.8% for Consumer Goods, +6.1% for Biz Equipment and +10.0% for Construction Supplies.

So much for soft vs hard data.

As a reminder (charts from EvergreenGavekal):

BTW, actual manufacturing sector orders increased 1.2% (+5.5% YoY) in January following +1.3% in December. We started to get some PMI reports for March and maybe we should take them all more seriously (charts from Haver Analytics):

The Philly Fed:

The NY Fed:

And if you think that consumer goods manufacturing remains “softâ€, think again if this trend in real sales continues:

And this is with a “soft†auto sector trying to work off its excess inventory.

BTW:

The University of Michigan said Friday that its preliminary reading of consumer sentiment rose to 97.6 in March, from February’s final reading of 96.3. It is up 7.3% from March 2016.

The recent rise in optimism reflects a turnaround from consumers’ attitudes in October, when sentiment had matched a two-year low.

The index reflecting sentiment on current economic conditions rose 2.7% from February to 114.5, the highest since November 2000.

Still, as in recent months, the survey remains divided along partisan political lines. Self-identified Democrats expect a deep recession while Republicans expect robust growth.

Sure seems that more republicans recently answered the survey than democrats! Read on.

(…) But the gaps in sentiment by income, employment and race are just as telling — and could help explain the recent tepid gains in household spending.

Since the election, the difference in sentiment between Americans earning more than $100,000 and those with incomes below $15,000 has reached its widest since the recession ended in 2009, according to data from the Bloomberg Consumer Comfort Index. (…)

Put another way, the poorest Americans are less confident today than the wealthiest Americans were at the nadir of the recession. (…)

Wealthy Americans, who own equities and other financial products, have seen substantial gains in assets recent months, while many Americans have not.

Another major divide is in employment. The confidence gap between employed and non-working Americans is at a record high in data going back to 1990 from the Consumer Comfort Index.

Sentiment among part-time and unemployed consumers hasn’t recovered to pre-recession highs, yet among full-time workers it’s the strongest since 2001, just as the Internet bubble was bursting. This all comes at a time when more Americans of prime working age are outside the labor force than during any economic expansion since the 1980s, which means that income gains go to a smaller swath of people. (…)

The broader gain in confidence is also uneven when looking along racial lines. While sentiment for black consumers typically runs slightly behind whites, since Trump’s election the gap has widened substantially, Consumer Comfort figures show. White confidence is now matching the strongest level in 15 years, while black sentiment recently sank to the lowest since 2014.

![]() So, looking for cracks in the economy, the “soft vs hard data†handle seems to have suddenly lost credibility. In fact, maybe economists and talking heads will soon be complaining that the data is too strong, that the economy is reaccelerating along with employment and wages and that the Fed is clearly behind the curve.

So, looking for cracks in the economy, the “soft vs hard data†handle seems to have suddenly lost credibility. In fact, maybe economists and talking heads will soon be complaining that the data is too strong, that the economy is reaccelerating along with employment and wages and that the Fed is clearly behind the curve.

On January 11, I suggested that we could be about to see a synchronized acceleration of global economies. Ten weeks later The Economist is front paging that as a reality (The global economy enjoys a synchronised upswing):

(…)

Now things are different. This week the Fed raised rates for the second time in three months—thanks partly to the vigour of the American economy, but also because of growth everywhere else. Fears about Chinese overcapacity, and of a yuan devaluation, have receded. In February factory-gate inflation was close to a nine-year high. In Japan in the fourth quarter capital expenditure grew at its fastest rate in three years. The euro area has been gathering speed since 2015. The European Commission’s economic-sentiment index is at its highest since 2011; euro-zone unemployment is at its lowest since 2009.

The bellwethers of global activity look sprightly, too. In February South Korea, a proxy for world trade, notched up export growth above 20%. Taiwanese manufacturers have posted 12 consecutive months of expansion. Even in places inured to recession the worst is over. The Brazilian economy has been shrinking for eight quarters but, with inflation expectations tamed, interest rates are now falling. Brazil and Russia are likely to add to global GDP this year, not subtract from it. The Institute of International Finance reckons that in January the developing world hit its fastest monthly rate of growth since 2011. (…)

As The Economist reminds us, “rarely has unemployment been this low without inflation taking off.†In my January 9 essay The Lady and the Trump, I quoted from Janet Yellen’s December 14 press conference:

- But, certainly, it’s important for households and businesses to understand that my colleagues and I have judged the course of the U.S. economy to be strong, that we’re making progress toward our inflation and unemployment goals. We have a strong labor market, and we have a resilient economy.

- So, with a 4.6 percent unemployment and a solid labor market, there may be some additional slack in labor markets, but I would judge that the degree of slack has diminished. So I would say at this point that fiscal policy is not obviously needed to provide stimulus to help us get back to full employment.

- I would say the labor market looks a lot like the way it did before the recession, that it’s—we’re roughly comparable to 2007 levels when we thought the, you know, there was a normal amount of slack in the labor market. The labor market was in the vicinity of maximum employment.

But I do want to make clear that I have not recommended running a “hot†economy as some sort of experiment.â€

But I do want to make clear that I have not recommended running a “hot†economy as some sort of experiment.â€

A more aggressive Fed would shake investor confidence and, perhaps, crack this resilient market. In the meantime, we are about to begin the Q1 earnings season and no dangerous cracks are showing there just yet:

EARNINGS WATCH

Earnings revisions on S&P 500 companies have turned positive last week:

Even though small and mid caps continue to see downward revisions:

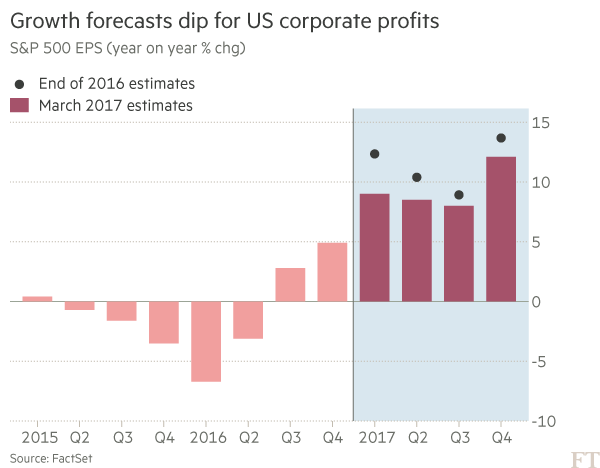

The FT has a negative slant:

-

Outlook for US corporate profits dims Analysts pare down forecasts for 2017 at a time when S&P 500 is at near record highs

But recent revisions are actually quite benign as RBC illustrates:

And pre-announcements are not giving any strongly negative signal so far.

A possible crack could erupt from Energy companies if energy prices remain softer than expected. Factset sees S&P 500 EPS rising 7.2% in Q1, down from +8.0% expected 3 months ago. However, if Energy companies don’t deliver, the growth rate could be cut in half.

-

Energy Shares Weigh on Markets as Oil Prices Slip European stocks and U.S. futures edged lower as a pullback in oil prices pressured shares of oil-and-gas companies.

Sometimes, cracks come directly from financial markets:

-

Stock Rally Faces Bond-Yield Threat The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note exceeded the dividend yield on the S&P 500—which over time stands to shift the preferences of investors who have been strongly skewed in favor of stocks.

(…) At 2.50%, the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note on Friday exceeded the 1.91% dividend yield on the S&P 500, according to FactSet. (…) the 10-year Treasury bond yield has spent much of the postcrisis period below the S&P dividend yield—something that as of 2008 hadn’t happened for roughly half a century. (…)

Net inflows to dividend-heavy exchange-traded funds have slowed for three straight weeks through March 8, to their lowest level since the week ending Jan. 18, according to data from fund tracker EPFR Global. (…)

(…) More often than not, forecasters incorrectly extrapolate recent trends for what will take place in the future. That is typically what prompts the surprise index to decline, with stocks often following suit.

Since 2003, stocks perform best in the three-month period leading up to when the Citi index hits a short-term peak. The S&P 500 often struggles when the surprise index trends lower from peak to trough, but then often rallies as the index turns higher again. (…)

But the better the economy does, the more optimistic forecasters get. That means it gets tougher for data to keep beating expectations, which makes it harder for the Citi index to keep rallying. (…) (chart from Ed Yardeni)

Cracks can also come from politics:

At the end of a meeting marked by trade tensions, finance ministers from the G20 countries issued a communiqué that failed to include language from last year vowing to “resist all forms of protectionismâ€. America’s treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, said the Trump administration had been “very clear that we do believe in free trade but we believe in balanced tradeâ€. (The Economist)

-

G20 ministers hit impasse with US over free trade Mnuchin refuses to budge on protectionist stance

(…) The US Treasury secretary, according to Germany’s finance chief Wolfgang Schäuble, appeared to have “no mandate†to settle his country’s position on one of the most pressing issues facing the G20 nations: free trade and protectionism. “We have reached an impasse,†Mr Schäuble said, later adding: “We did go to great lengths, we tried everything, we went down many avenues together and unilaterally.†(…)

For some G20 partners the refusal of the US to commit itself clearly to free trade marked the first step down a dangerous road. (…)

There is still hope among advocates of free trade that moderate voices in the Trump administration will gain influence. (…)

Hmmm…so far it seems the hawks are winning:

Inside Trump’s White House, New York moderates spark infighting and suspicion Business elites are ascendant in Trump’s orbit, inflaming tensions with Bannon, Priebus.

Hence:

Lastly:

-

GOP Infighting, Trump’s Comments Test President’s Early Agenda Halfway through President Trump’s first 100 days in office, controversies and legislative infighting are impeding the momentum of the White House toward some of its more ambitious agenda items.

-

From Gallup via The Daily Shot: